Classical Biological Control of Asian Citrus Psyllid in Florida

By: Marjorie A. Hoy, Ru Nguyen, and A. Jeyaprakash

The Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri, has successfully invaded Florida and is expected to colonize the entire state. By the time the pest was detected in June 1998 in Florida, D. citri had spread through a sufficiently large region of the southeastern citrus-growing area that it was not considered amenable to eradication efforts. Also, no effective eradication methods were known. By June 1999, this pest had spread to 12 counties in Florida, including Brevard, Broward, Collier, Dade, Hendry, Indian River, Martin, Monroe, Orange, Osceola, Palm Beach, and St. Lucie. D. citri will likely colonize the rest of the citrus-growing region in Florida and could spread to Louisiana, Texas, Arizona, and California citrus. In addition to commercial citrus, the ornamental plant orange jasmine, Murraya paniculata, is a suitable host for this pest.

Asian citrus psyllids cause economic damage to citrus in groves

and nurseries by direct feeding and, potentially, by transmitting

a serious citrus disease called greening. Both adults and nymphs

feed on young foliage, depleting the sap and causing galling or curling

of leaves. High populations feeding on a citrus shoot can kill the

growing tip. They produce honeydew, which allows the growth of sooty

mold. More importantly, this psyllid is able to transmit an endocellular,

phloem-restricted bacterium, Liberobacter asiaticum, that causes

greening disease. The disease also is called Huanglongbing or yellow

shoot in China, citrus Likubin (decline in Taiwan), dieback in India,

or leaf mottle in the Philippines.

Asian citrus psyllids cause economic damage to citrus in groves

and nurseries by direct feeding and, potentially, by transmitting

a serious citrus disease called greening. Both adults and nymphs

feed on young foliage, depleting the sap and causing galling or curling

of leaves. High populations feeding on a citrus shoot can kill the

growing tip. They produce honeydew, which allows the growth of sooty

mold. More importantly, this psyllid is able to transmit an endocellular,

phloem-restricted bacterium, Liberobacter asiaticum, that causes

greening disease. The disease also is called Huanglongbing or yellow

shoot in China, citrus Likubin (decline in Taiwan), dieback in India,

or leaf mottle in the Philippines.

Greening is considered the most serious disease of citrus in the world, causing reduced production and death of trees. Classical biological control of the psyllid vector should contribute to the suppression of psyllid populations. The resultant lower psyllid populations could reduce the rate of transmission of greening if the disease is confirmed to be present in Florida.

Our goal is to release two natural enemy species of the Asian citrus psyllid in Florida. The first natural enemy to be released is an ectoparasitoid, Tamarixia radiata (Waterston) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). This parasitoid was obtained from Taiwan and Vietnam and evaluated in the high security quarantine at the Division of Plant Industry, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Gainesville, Florida beginning in October, 1998. No plant material or psyllid hosts were imported to reduce the chance that the parasitoids would be contaminated with the greening disease organism. In addition, parasitoids were reared on psyllids reared on orange jasmine (which is considered an unsuitable host for greening disease). Permission to release T. radiata was obtained on July 12, 1999 and the first releases took place on July 15, 1999 near Fort Pierce.

Once in quarantine, the parasitoids were tested during more than 12 generations with a molecular method called the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and all were negative for greening disease. In all tests conducted on the parasitoids, only the positive controls were positive. By contrast, a survey of citrus trees in south Florida by the PCR suggests that the greening disease organism's DNA is already present in Florida citrus, even though the trees do not show obvious symptoms of the disease (S. Halbert, personal communication). Our sensitivity analysis of the PCR test indicated that we could detect as few as 100 copies of the greening disease DNA if it is present in either psyllids, parasitoids, or citrus plants. Additional research by plant pathologists is needed to confirm the presence of the greening disease bacterium in citrus in Florida. However, our PCR results indicate that releases of the parasitoid T. radiata will not introduce greening disease into Florida because they are negative for greening DNA.

The parasitoids will be released throughout the areas of Florida that have Asian citrus psylla. Release sites should have abundant psyllid hosts and not be treated with toxic pesticides and will include orange jasmine plants, door yard citrus, and groves. Once releases are made, establishment and dispersal of the parasitoids will be monitored periodically. Releases will consist of 100-200 parasites per release per site.

Native natural enemies in Florida may contribute to the suppression of Asian citrus psyllid, although we know little about which natural enemies will attack this pest in Florida at present. In China, the lacewing Chrysopa boninensis is considered an important natural enemy of the psyllid and fungal pathogens have been reported to reduce psyllid populations when the relative humidity is high. Spiders and other generalist natural enemies could prey on the psyllids, as well.

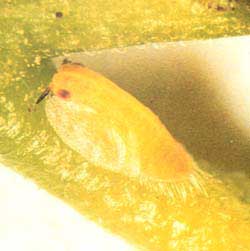

The parasitoid Tamarixia radiata previously was introduced into the islands of Reunion, Mauritius, and Taiwan, where it has performed well. T. radiata appears to be a very effective parasitoid, producing nearly two generations for each pest generation. T. radiata females live 12 to 24 days and deposit 166 to 330 eggs. Females deposit eggs on the psyllid nymph between the thorax and abdomen. The newly hatched parasitoid larva sucks fluid from the site where it is attached to the host, eventually killing it. By the time the T. radiata larva has matured it has sucked out the contents of the psyllid and the psyllid has become 'mummified' and turns a dark brown color. The adult parasitoid emerges from the top of the thorax, leaving a distinctive emergence hole.

T. radiata females also kill all stages of psyllids by host feeding (which means females insert their ovipositor into the psyllid to make a hole and then suck up the liquid that oozes out). Host feeding provides a source of protein that helps the female parasitoid produce more eggs. T. radiata females also feed on honeydew excreted by the psyllids. A single T. radiata female is able to kill over 500 psyllids by a combination of host feeding and parasitism.

While T. radiata has a short generation time and high reproductive rate in the laboratory, its effectiveness in suppressing psyllid populations under field conditions needs further analysis, especially under Florida's conditions. In Taiwan, T. radiata performed best in relatively stable habitats (orange jasmine plantings with no pesticides and little large-scale pruning); under these conditions T. radiata and another parasitoid, D. aligarhensis, were able to maintain psyllids at low levels. In a less stable habitat (when orange jasmine was pruned every three to four months and pesticides were applied occasionally), psyllid densities were higher and parasitism was lower. In the most disturbed habitat (if citrus trees were treated with methomyl), the parasitoids were unable to persist.

T. radiata is expected to establish in Florida but it could take a year or two to confirm its establishment, overwintering success, and ability to spread.

Read more about the Asian citrus psyllid, the parasitoids, and greening disease at:

http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/citrus/acpsyllid.htm

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Florida Citrus Research Advisory Committee; the Davies, Fischer and Eckes Endowment in Biological Control; the Division of Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services; and the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. M. A. Hoy and A. Jeyaprakash are in the Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 and R. Nguyen is in the Division of Plant Industry, Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Gainesville, FL. We thank Dr. K.C. Lo (Taiwan) for assistance in obtaining T. radiata and L. Skelley for her expert assistance in rearing.